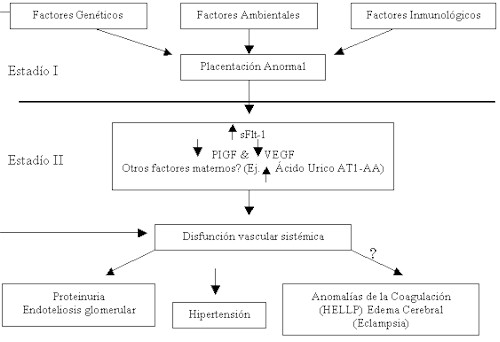

Figura 2. Patogenia de la preeclampsia. Resumen de los mecanismos implicados en ella. Tomado de 7.

El síndrome materno en la preeclampsia, corresponde a un estado de disfunción endotelial generalizado secundario a un exceso de factores tóxicos para el endotelio (como el sFlt-1) los cuales son liberados por la placenta patológica o enferma. La comprensión de los mecanismos que conducen a la isquemia placentaria en la preeclampsia debería aclararnos sobre la patogenia de la misma. Los estudios futuros deberán caracterizar las diversas proteínas circulantes elaboradas por la placenta isquemica y comprender su interacción con los factores patológicos ya identificados tales como el AT1-AA, el ácido urico y el sFlt-1. Los estudios genéticos multicentricos en curso (como el GOPEC, Genetic of pre-eclampsia) nos podrían informar sobre la importancia de los factores de predisposición genética y la preeclampsia (49). Bien que los progresos de la obstetricia y neonatología han reducido considerablemente la morbi mortalidad de la preeclampsia (especialmente en los países desarrollados) no ha existido una verdadera revolución terapéutica en el tratamiento de la preeclampsia en los últimos 40 años. Los resultados iniciales prometedores del tratamiento por la aspirina y el suplemento de calcio no han sido confirmados en extensos estudios randomizados (50,51). Las tentativas terapéuticas con la intención de restaurar la función endotelial con agentes como el VEGF, el PIGF, las prostaciclinas, deberían utilizarse en las pacientes portadoras de una enfermedad severa para esperar retardar el parto sin poner en peligro la madre. Las complicaciones a largo plazo cardiovasculares y metabólicas en las mujeres con preeclampsia se deben clarificar.

REFERENCIAS

1.Robert JM, Cooper DW. Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia,Lancet 2001; 357: 53-56.

2.Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, Lie RT. Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study, Br Med J 2001; 323: 1213-17.

3.Dekker GA. Risk factors for preeclampsia, Clin Obstet Gynecol 1999; 42: 422-435.

4.Page EW. The relation between hydatid moles, relative ischemia of the gravid uterus and the placental origin of eclampsia, Am J Obstet Gynecol 1939; 37: 291.

5.Robert JM. Preeclampsia: what we know and what we do not know, Semin Perinatol 2000; 24: 24-8.

6.Robert JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rodgers GM, Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK. Preeclampsia: an endothelial cell disorder, Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989; 161: 1200-04.

7.Karumanchi SA, Lam C. Mécanismes impliqués dans la pré-éclampsie: progrès récents. In: Lesavre P, Drüke T, Legendre P, Niaudet P, editors.Actualités Néphrologiques de l'Hopital Necker Jean Hamburger. Paris: Flammarion Médecine-Sciences; 2004.p.167-76.

8.Khong TY, De Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and by small-for-gestational age infants, Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1986; 93: 1049-59.

9.Gerretsen G, Huisjes HJ, Elema JD. Morphological changes of the spiral arteries in the placental bed in relation to pre-eclampsia and fetal growth retardation, Br Obstet Gynaecol 1981; 88: 876-81.

10.Casper FW, Seufert RJ. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) in preeclampsia-like syndrome in a rat model, Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 1995; 103: 292-96.

11.Brosens IA, Robertson WB, Dixon HG. The role of the spiral arteries in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, Obstet Gynecol Amn 1972; 1: 177-91.

12.Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension, Science 1997; 277: 1669-72.

13.Fisher SJ, Damsky CH. Human cytotrophoblast invasion, Semin Cell Biol 1993; 4: 183-88.

14.Zhou Y, Fisher SJ, Janatpour M, Genbacev O, Wheelock M et al. Human cytotrophoblast adopt a vascular phenotype as they differentiate. A strategy for successful endovascular invasion ?, J Clin Invest 1997; 99: 2139-51.

15.Lim KH, Zhou Y, Janatpour M, McMaster M, Bass K, Chun Sh et al. Human cytotrophoblast differentiation/invasion is abnormal in pre-eclampsia, Am J Pathol 1997: 151: 1809-18.

16.ZhouY, Genbacev O, Fisher SJ. The human placenta remodels the uterus by using a combination of molecules that govern vasculogenesis or leukocyte extravasation, Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003; 995: 73-83.

17.Zhou Y, McMaster M, Woo K, Janatpour M, Perry J, Karpanen T et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor ligands and receptors that regulate human cytotrophoblast survival are dysregulated in severe preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome, Am J Pathol 2002; 160: 1405-23.

18.Genbacev OD, Prakobphol A, Foulk RA, Krtolica AR, Ilic D, Singer MS et al. Trophoblast L-selectin-mediated adhesion at the maternal-fetal interface, Science 2003; 405-08.

19.Moffett-King A. Natural killer cell and pregnancy, Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 656-63.

20.De Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I. The ultrastructure of acute atherosis in hypertensive pregnancy, Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975; 123: 164-74.

21.Roberts JM. Endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia, Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1998; 16: 5-15.

22.Friedman SA, Schiff E, Emeis JJ, Dekker GA, Sibai BM. Biochemical corroboration of endothelial involvement in severe preeclampsia, Am Obstet Gynecol 1995; 172: 202-203.

23.Cokell AP, Poston L. Flow-mediated vasodilatation is enhanced in normal pregnancy but reduced en preeclampsia, Hypertension 1997: 30: 247-51.

24.Mills JL, DerSimonian R, Raymond E, Morrow JD, Roberts LJ, Clemens JD et al. Prostacyclin and thromboxane changes predating clinical onset of preeclampsia: a multicenter prospective study. JAMA 1999: 282: 356-62.

25.Fisher KA, Luger A, Spargo BH, Lindheimer MD. Hypertension in pregnancy: clinical-pathological correlations and remote prognosis, Medicine 1981; 60: 267-76.

26.Roberts JM. Edep ME, Goldfien A, Taylor RN. Sera from preeclamptic women specifically activate human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro: morphological and biochemical evidence, Am J Reprod Immunol 1992; 27: 101-08.

27.Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, Frolich JC, Vallance P, Nicolaides KH. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentration of asymetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently developed preeclampsia, Lancet 2003; 361: 1511-17.

28.Page NM, Woods RJ, Gardiner SM, Lomthaisong K, Gladwell RT, Butlin DJ et al. Excessive placental secretion of neurokinin B during the third trimester causes pre-eclampsia, Nature 2000; 405: 797-800.

29.AbdAlla S, Lother H, el Massiery A, Quitterer U. Increased AT (1) receptor heterodimers in preeclampsia mediate enhanced angiotensin II responsiveness, Nat Med 2001; 7: 1003-09.

30.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia, J Clin Invest 2003: 111: 649-58.

31.Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a critical cytokine in tumor angiogenesis and a potential target for diagnosis and therapy, J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 4368-80.

32.He Y, Smith SK, Day KA, Clark DE, Licence DR, Charnock-Jones DS. Alternative splicing of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-R1 (FLT-1) pre-mRNA is important for the regulation of VEGF activity, Mol Endocrinol 1999; 13: 537-45.

33.Kendal RL, Thomas KA. Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 705-09.

34.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J,Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia, J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 649-58.

35.Koga K, Osuga Y, Yoshino O, Hirota Y, Ruimeng X, Hirata T et al. Elevated serum soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (sVEGFR-1) levels in women with preeclampsia, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 2348-51.

36.Polliotti BM, Fray AG, Saller DN, Mooney RA, Cox C, Miller RK. Second-trimester maternal serum placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor for predicting severe, early-onset preeclampsia, Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 101: 1266-74.

37.Taylor RN, Grimwood J, Taylor RS, McMaster MT, North RA. Longitudinal serum concentrations of placental growth factor: evidence for abnormal placental angiogenesis in pathologic pregnancies, Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 188: 177-82.

38.He H, Venema VJ, Gu X, Venema RC, Marrero MB, Caldwel RB. Vascular endothelial growth factor signals endothelial cell production of nitric oxide and prostacyclin through flk-1/KDR activation of c-Src, J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 25130-135.

39.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer, N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 427-34.

40.Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, Lindschau C, Horstkamp B, Jupner A et al. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin AT1 receptor, J Clin Invest 1999; 103: 945-52.

41.Xia Y, Wen H, Bobst S, Day MC, Kellems RE. Maternal autoantibodies from preeclamptic patients activate angiotensin receptors on human trophoblast cells, J Soc Gynecol Investig 2003; 10: 82-93.

42.Dechend R, Viedt C, Muller DN, AT1 receptor agonistic antibodies from preeclamptic patients stimulate NADPH oxidase, Circulation 2003; 107: 1632-39.

43.Kang DH, Finch J, Nakawa T, Karumanchi SA, Kanellis J, Granger J et al. Uric acid, endothelial dysfunction, and preeclampsia: searching for a pathogenetic link, J Hyperten 2003; 22: 229-35.

44.Schaffer N, Dill L, Cadden J. Uric acid clearance in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia, J Clin Invest 1943; 22: 201-06.

45.Many A, Hubel CA, Roberts JM. Hyperuricemia and xanthine oxidase in preeclmapsia, revisited, Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 288-91.

46.Weerasekera DS, Peiris H. The significance of serum uric acid, creatinine and urinary microprotein levels in predicting pre-eclampsia, J Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 23: 17-19.

47.Redman CW, Bonnar J. Plasma urate changes in pre-eclampsia, Br Med J 1978; 1: 1484-85.

48.Nakagawa T, Mazzali M, Kang DH, Kanellis J, Watanabe S, Sanchez-Lozada LG et al. Hyperuricemia causes glomerular hypertrophy in the rat, Am J Nephrol 2003; 23: 2-7.

49.Lachmeijer Am, Dekker GA, Pals G, Aarnoudse JG, ten Kate LP, Arngrimsson R. Searching for preeclampsia genes: the current position, Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002; 105: 94-113.

50.Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, Lindheimer MD, Klebanoff M, Thom E et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in womwn at high risk, N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 701-05.

51.Levine RJ, Hauth JC, Curet LB, Sibai BM, Catalano PM, Morris CD et al. Trial of calcium to prevent preeclampsia, N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 69-76.

Patogenia de la preeclampsia: avances recientes. Una revisión

Miguel Rondon Nucete, Ana Verónica Rondon Guerra.

Unidad de Nefrología, Diálisis y Trasplante Renal, Departamento de Medicina, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida, Venezuela